Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace, Middlesex:

This is the most splendid and magnificent royal palace that may be found in England or indeed in any other kingdom.

Jacob Rathgeb 1592

To walk the grounds and corridors of Hampton Court Palace is to walk in the footsteps of all Tudor kings and queens. Within the Tudor palace’s russet-coloured walls, the present fades into the brickwork, and the past emerges to greet us.

Hampton Court Palace is a place that Anne Boleyn would have known well, both before and after becoming queen. Although much of the Tudor palace has, over the years, been modified or demolished and replaced with William III and Mary II’s baroque palace, the buildings that survive propel us back through the years to a time when Hampton Court was one of Henry VIII’s most beloved palaces, at the centre of court life and politics.

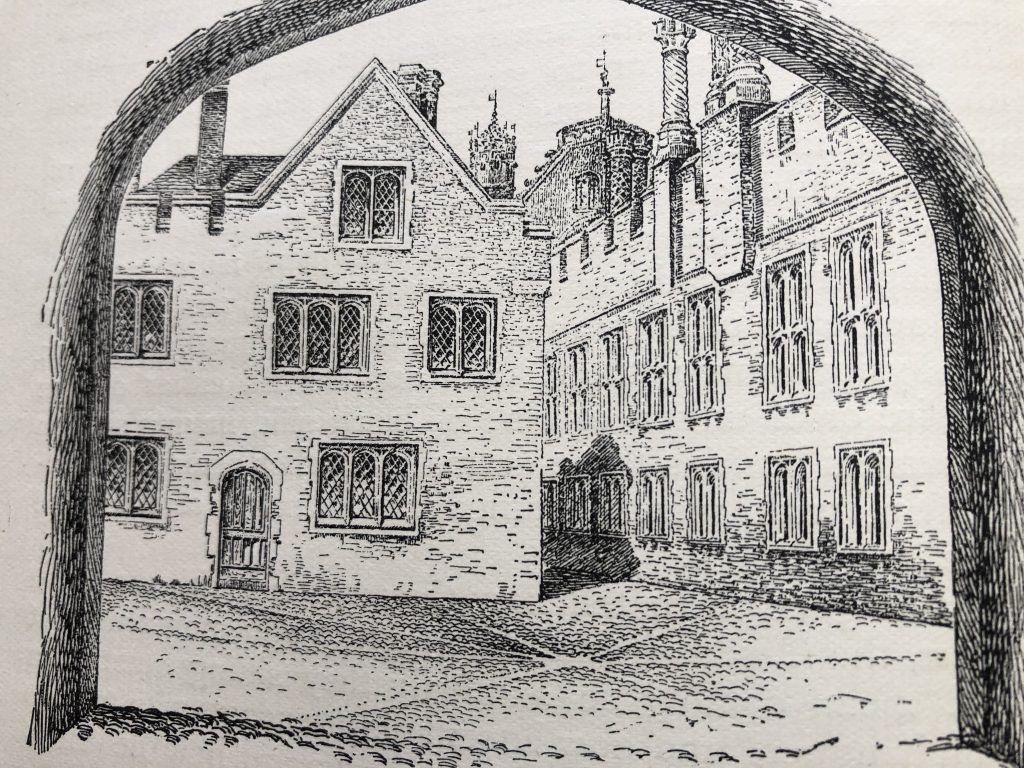

Base Court; Original 5-storey gatehouse; Clock Court.

A Brief History of Hampton Court

Initially built for Cardinal Wolsey as a house for entertaining royalty, foreign ambassadors and dignitaries, its magnificence reflected his status as Cardinal and Lord Chancellor of England. Wolsey built new kitchens, courtyards, lodgings, galleries, and gardens and began work on the chapel. He also built luxurious apartments for Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon and the Princess Mary on the site of the present-day Cumberland Suite, part of the later Georgian Rooms.

Henry VIII took complete possession of Hampton Court in 1529. He embarked on an enormous building campaign attested to by the six-and-a-half-thousand-page building accounts that survive in the Public Record Office.

Anne’s Apartments at Hampton Court

Anne had her own lodgings at Hampton Court as early as June 1529, where it is said Henry kept her ‘more like a queen than a simple maid’; unfortunately, the precise location is unknown. We do know that Henry and the newly crowned Queen Anne visited in July 1533 when the queen’s new lodgings, designed expressly for Anne, were only being excavated. These lavish apartments were to be built on the east side of a new courtyard overlooking the park. Beneath the lodgings would be a wardrobe for Anne’s clothes, a privy kitchen and a nursery for the prince they hoped Anne was carrying.

The external appearance of these new rooms can be seen on several early views of the east front of the palace; they stood in the area now known as Fountain Court but were demolished in the late seventeenth century to make way for Sir Christopher Wren’s baroque palace. Given that the apartments were not completed until early 1536, Anne needed to stay in the old queen’s lodgings, those built by Wolsey for Katherine of Aragon, from where she would have been able to see how the work was progressing on the new wing.

The royal couple visited again in December 1533, in the early summer of 1534 and again in July 1534, the same month that George Boleyn was asked to ‘repair to the French king with all speed’ to defer a meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I because Anne was ‘far gone with child’ and not able to travel.

On the other side of Anne Boleyn’s Gate lies another inner courtyard, an area known as Clock Court.

© The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Tragedy of July-August 1534

Hampton Court was likely the backdrop to one of the most emotional and dramatic moments in Anne’s life. But to understand this connection, we must look at what we know of Anne Boleyn’s second pregnancy.

As early as January 1534, Anne is reported as being ‘again in the family way’. Her receiver-general recorded in late April that the queen had a ‘goodly belly ’. Then, on 26 June, we hear in a further letter, this time sent from Sir Edward Ryngeley to Lord Lisle, that the couple were ‘merry’. No doubt the king was hunting daily whilst Anne was careful to rest; at seven to eight months pregnant, she would soon be expected to be taking to her chambers.

However, quite suddenly, on 2 July, the king seems to have left Anne behind and moved to the More, where he summoned Anne’s uncle, the Duke of Norfolk and Thomas Cromwell to meet him on 5 July. Shortly thereafter, it was announced that the trip to Calais to meet with the French king, which had been long arranged for the forthcoming autumn, was cancelled. Almost immediately, George Boleyn was ordered to go to France in all haste to delay the planned meeting with Francis I, using the excuse that Anne’s advanced pregnancy prevented her from travelling overseas.

The only historian that the authors have come across who has gone into these perplexing events in any detail is Rethe Warnike in The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn, who postulates that sometime between 26 June and 2 July, Anne delivered a stillborn child. The king, who was no doubt both devastated and furious at Anne’s failure, summarily left her at Hampton Court.

No longer able to face Francis, who was already the father of three healthy sons, a cover story was created to save face, and the whole event was swept under the carpet. In the end, we even hear through Chapuys that rumour had it at court that Henry had begun to doubt whether the queen had ever been pregnant. The king had been misled and was free of all stain – how convenient!

It’s conceivable then, considering that Henry and Anne were at Hampton Court in late June to early July, that she was at Hampton Court when she lost the baby, remaining there to rest and recuperate while Henry commenced his summer progress.

In mid-March 1535, the couple returned. Unbeknown to Anne, this visit would be her last, for the following year, in May 1536, Anne was charged with twenty-one acts of adultery. One of these was alleged to have occurred at Hampton Court Palace on December 8 1533, with a gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, William Brereton.

This is not the place to discuss Anne’s fall except to say that historians over the years have successfully demonstrated that the case presented by the Crown in May 1536 against Anne and the five men accused with her is, at best, flimsy and, under close analysis, collapses.

After this final visit in March 1535, and probably due to the massive building works taking place, Henry absented himself and appears not to have visited at all between April 1535 and May 1537. He would return on 8 May 1537 with his third wife, Jane Seymour.

The queen’s new lodgings were not in full use until October 1537, so Anne Boleyn, like her successor, Jane, did not live to enjoy her lavish new apartments.

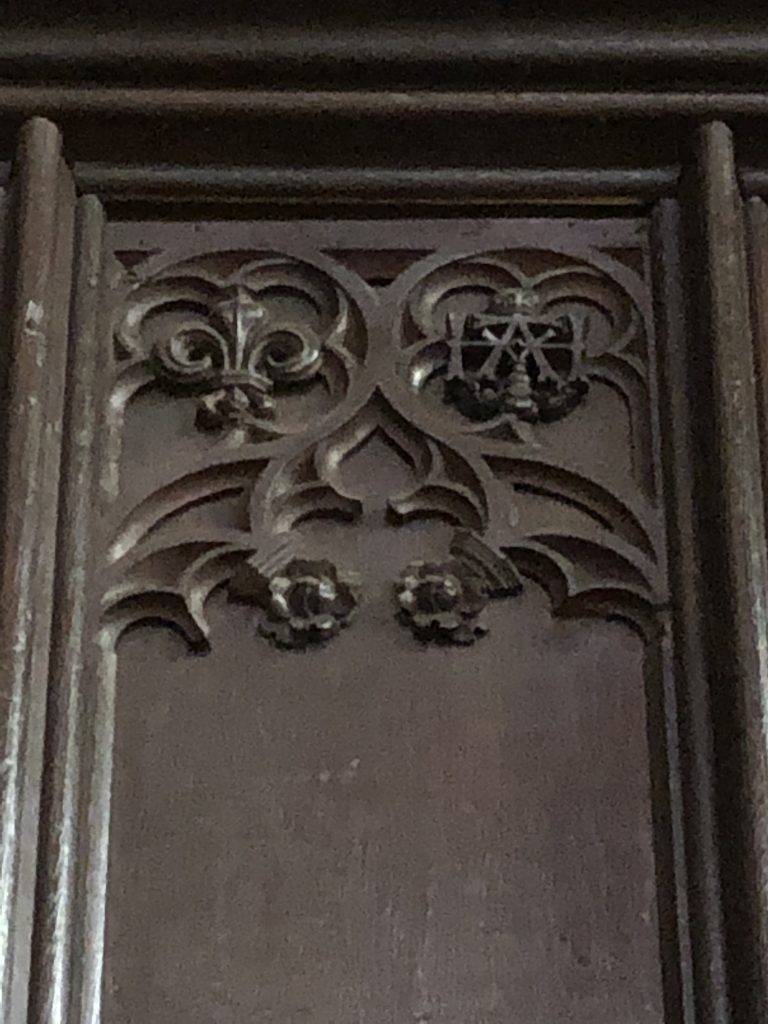

Decorative spandrel leading through into the old Queen’s apartments, © The Tudor Travel Guide;

Service Court; Clock Court.

Visiting Hampton Court Palace Today

The main entrance is via the west front, begun by Cardinal Wolsey and completed for Henry VIII. Wolsey’s gatehouse was originally five stories high, rather than the three that we see today, but it was found to be unstable, and so reduced in the eighteenth century.

On the turrets, either side of the gatehouse, are terracotta roundels with the heads of the Roman emperors Tiberius and Nero. These were found in a cottage in Windsor Park by the Victorian Surveyor, Edward Jesse, and were probably originally from the Holbein Gate at Whitehall, where in an upper chamber over the gate, Anne Boleyn married Henry VIII in January 1533. Two similar roundels survive from the now-lost Hanworth Manor, bestowed upon Anne in 1532.

The bridge to the central gateway is lined with ten heraldic beasts supporting the royal arms, including the Tudor dragon and the queen’s lion. These are modern replacements of the originals that once stood here. Look up above the central gateway, and on a carved panel are the arms of Henry VIII.

Stepping into Base Court feels very much like time travel. It is much as it was when Wolsey built it to house his guests and large household. Anne would undoubtedly recognise it today. Each of the thirty double guest lodgings had an outer and inner room with a garderobe (toilet) and fireplace. The epitome of sixteenth-century luxury!

The four-metre high, re-created Tudor wine fountain in this courtyard is built on the very spot where Henry VIII’s octagonal fountain once stood and testifies to Hampton Court’s role as a pleasure palace. The design is based on the fountain visible in the Field of Cloth of Gold painting and is engineered to serve real wine on special occasions.

Those of us in search of the last vestiges of the reign of Queen Anne Boleyn should proceed to Anne Boleyn’s Gatehouse.

Heraldic beasts; Replica wine fountain in the inner courtyard at Hampton Court Palace; Base Court.

© The Tudor Travel Guide. © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Anne Boleyn’s Gatehouse

This name dates from the nineteenth century when the vault beneath the gateway was reconstructed. The ceiling is decorated with Henry and Anne’s entwined initials and Anne’s falcon badge; sadly, these are not original but Victorian replicas. The good news is that a stone falcon badge from the original vault is on display in the great hall, where you should proceed next.

The entry to Henry VIII’s state apartments is up the staircase under Anne Boleyn’s Gateway, which takes you into the magnificent great hall. Just before the hall, the doorway leading into the buttery is decorated with Tudor roses for Henry VIII and Spanish pomegranates – Katherine of Aragon’s personal badge.

Carved H & A; Decorative spandrel, part of the door frame leading through into the old Queen’s apartments.

© The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Great Hall

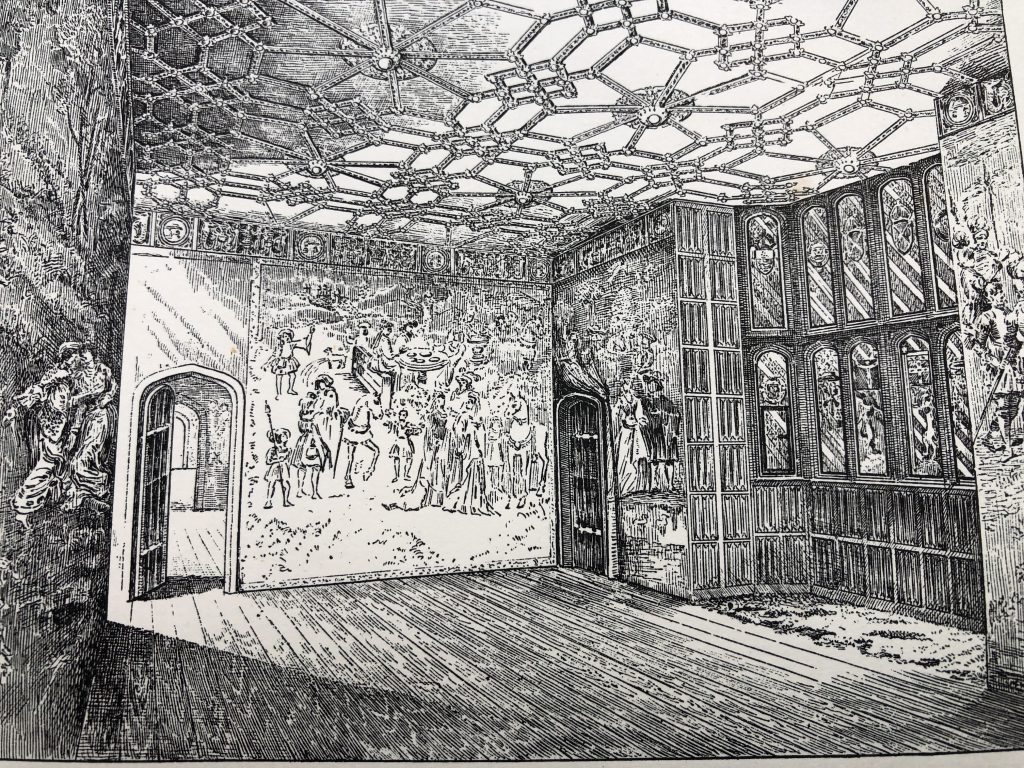

The great hall is majestic and breathtaking. The splendid hammer-beam roof is decorated with royal arms, badges, and a series of carved and painted heads. In Anne’s day, the floor would have been paved with tiles and the roof painted blue, red and gold.

Today’s hall is hung with priceless Flemish tapestries of the Story of Abraham commissioned by Henry VIII and woven in the 1540s with real silver and gold thread. A series of six hangs in the great hall, one of which – The Oath and Departure of Eliezer – was hung in Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Elizabeth I. The tapestries have faded, but you can still see how vibrant and splendid they would have been when first woven.

Anne took a great interest in the building works at Hampton Court, and on the ceiling, you can still see Henry and Anne’s entwined initials and Anne’s falcon badge. As you enter the hall, the wooden screen behind you is carved with Anne and Henry’s interlocking initials – all serving as a poignant reminder of her brief reign. After Anne’s arrest and execution, Henry ordered all her badges removed and replaced with Jane Seymour’s ones. Luckily for us, in the frenzy to eradicate all memory of Henry’s fallen queen, those less accessible were overlooked.

The great watching chamber was originally the first of Henry VIII’s state apartments, and its principal function in Henry’s reign was as a dining room for household officials. The door at the far end of the room once led to the king’s presence chamber and state apartments, sadly, now lost. This door would have been heavily guarded, and only those close to the king, including Anne, would have been permitted entry.

Although beautiful, the stained glass window in this chamber is not original, and the Tudor fireplace and great heraldic frieze that once decorated the walls above the tapestries are long gone. However, the splendid ceiling, decorated with the arms of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, and the tapestries are original.

The Great Hall; Stairs leading up to The Great Hall. © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Horn Room, the Council Chamber and the Haunted Gallery

The Horn Room was initially used as a waiting area for servants bringing food from the Tudor kitchens directly below, up to the great hall and great watching chamber. The balustrade is Victorian. However, the original Tudor oak steps survive.

Further down the gallery is King Henry VIII’s council chamber, opened to the public for the first time in April 2009. It is worth pausing here for a moment to consider that in this very room, Henry VIII discussed and debated important matters of state, making many historic decisions within its four walls. Like so many of the chambers at Hampton Court, the energetic imprint of those who have passed through this space, Norfolk, Suffolk, Cromwell, Thomas Boleyn and Henry himself, is tangible; you can almost hear their voices speaking to you across time. When we were there, a brief glimpse out of the window into the courtyard below catapulted us back in time. For there, walking through the gardens, were two Tudor noble ladies. It was pretty disorientating but a wonderful snapshot of a lost era.

From here, proceed to the upper chapel cloister, better known as the Haunted Gallery (see author’s note below), built by Cardinal Wolsey to connect the chapel to the rest of the palace. It is home to some wonderful tapestries and paintings, including The Family of Henry VIII by an unknown artist, c. 1545. Look closely at the ‘A’ necklace adorning the neck of the Princess Elizabeth, as it’s said to have belonged to her mother. From the Haunted Gallery, you can access the royal pew; from here, Anne would have sat and looked down into the body of the chapel.

In Tudor times, the king and queen had separate rooms in the royal pew, with windows looking down into the chapel choir. Henry VIII installed the magnificent vaulted ceiling that you see today in 1535-6, replacing an earlier ceiling added by Cardinal Wolsey, who built the body of the chapel.

Originally, a great double window at the east end would have been filled with stained glass. In October 1536, the window was re-glazed to remove the figure of St Anne, the mother of Mary, installed initially as a way of linking Queen Anne with the Virgin. The glass was removed in the eighteenth century, and the window was hidden behind the current wooden reredos.

It is in this chapel that Prince Edward, Henry VIII’s long-awaited son, was christened in October 1537. In the king’s closet, within the Chapel Royal, Henry married his sixth and final wife, Katherine Parr, in the presence of his two daughters, the Princesses Elizabeth and Mary. If only walls could talk!

As you exit the chapel into the north cloister, note Henry VIII and Jane Seymour’s coat of arms flanking the chapel door. Although almost certainly moved from another part of the palace, these two heraldic plaques once held Cardinal Wolsey’s arms and hat, which were repainted by Henry VIII after 1530.

The Great Watching Chamber; Roundel from the Great Watching Chamber. Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Henry’s Lost Privy Apartments – The Cumberland Suite

The Georgian Rooms may seem like they have nothing to offer the Tudor enthusiast. Still, as mentioned earlier, it is precisely on the site of the present-day Cumberland Suite that Wolsey built the state apartments that Anne and Henry stayed in while awaiting the completion of their new lodgings. Remember the door at the far end of the great watching chamber? This once opened into Henry’s presence chamber and private apartments, with Anne’s apartments positioned directly above the king’s on the second floor.

The three-storey range was initially designed to house the Princess Mary on the lower level, Henry on the first floor and Katherine directly above him. The Queen’s apartments contained three large rooms, the entrance to which still survives, although sadly, it is not accessible to the public. A surviving doorway on this level depicts Wolsey’s arms on one spandrel and the royal arms on the other. A few more remnants of its Tudor past exist, including a large chimneypiece containing Wolsey’s badges and mottoes and a door leading to a closet.

In 1537, Jane Seymour occupied the same ‘old lodgings’ as her two predecessors and gave birth to Prince Edward in one of the rooms. She would never recover from the birth of her precious son, and twelve days later, she died. Perhaps this is the same room in which Anne was delivered of a stillborn baby in late June/early July 1534.

This range was entirely rebuilt in the eighteenth century. Only Wolsey’s great spine wall with its fireplaces and closets remains. Make your way into the room containing a sizeable recessed alcove with two smaller ones on either side. In one of the alcoves, in the far corner, is a bricked-up doorway that once connected the king’s private chambers directly with Wolsey’s gallery and apartments.

If you are lucky, and ask nicely as we did, one of the guides may show also you the surviving Tudor spiral staircase that once led to Henry VIII’s wardrobe. Every morning, Henry’s clothes would be brought up these stairs from the wardrobe below and handed to the gentlemen of the privy chamber, who were responsible for dressing the king.

The buildings on the right were the original royal lodgings; Princess Mary’s lodgings on the ground floor; the king’s on the first and the queen’s on the upper floor. Image by Elliott Brown via Wikimedia Commons Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic.

The Wolsey Closet and Rooms

Beyond the Cumberland Suite, the Wolsey Closet gives visitors a good idea of what a small closet might have looked like during Anne’s reign. Although heavily restored in the nineteenth century, conservation revealed that part of the ceiling, dating from the late 1530s, has remained in situ. The ceiling is decorated with gilded Renaissance motifs and badges incorporating the Tudor rose.

Further evidence of Hampton Court’s Tudor past can be found in the Wolsey Rooms (currently closed – 2023), believed to have been Wolsey’s private lodgings in the 1520s. It is also thought that Princess Mary (later Queen Mary) and Katherine Parr may have also stayed or entertained here.

Like so much of Hampton Court Palace, the rooms have been modified and altered over time. Still, some original Tudor features have survived: sixteenth-century linenfold panelling lines the walls of the two smaller rooms, the plain Tudor fireplaces date from Wolsey’s time, the ribbed ceilings in the two main rooms incorporate early Renaissance motifs, and the ceiling of the end room incorporates Wolsey’s badges.

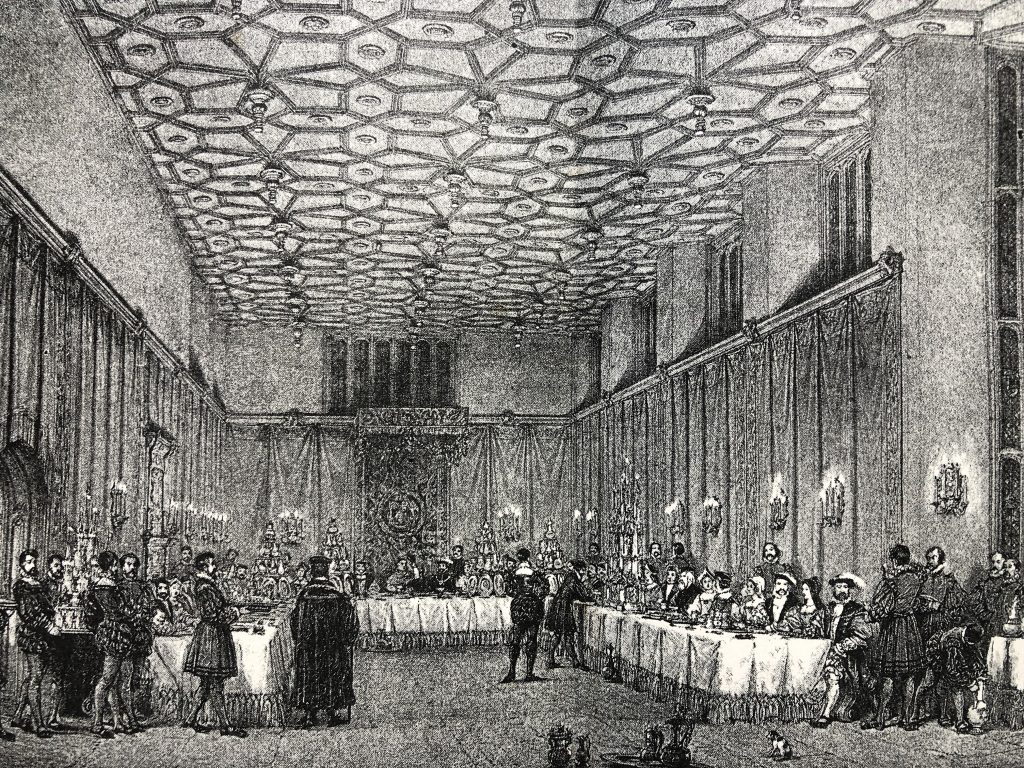

Wolsey dines in his great watching chamber; Line drawings of the Wolsey Rooms.

The Palace Kitchens and the Tiltyard

No visit to Hampton Court Palace is complete without a tour of the Tudor Kitchens. Built partly by Lord Daubeney, who owned Hampton Court before Wolsey and extended by Henry VIII in 1529, they were designed to feed the royal household, which could number up to 800 people in the wintertime. The court dined in the great hall and watching chamber twice daily.

Today, the smell of woodsmoke from the fire burning in the great kitchens awakens memories of a distant past. The crowds of tourists that pack the kitchens during peak times evoke a sense of the hustle and bustle of the 200 strong staff that manned this vast operation during Henry’s reign.

Royal dishes were prepared in a separate or privy kitchen by the king and queen’s cook and personnel. From 1529 until 1537, Henry’s private kitchen was situated beneath his lodgings and survives, albeit in a much-altered state, on the ground floor below the Wolsey Closet.

And while on the topic of food…the Privy Kitchen (a café) is housed in what was once Elizabeth I’s private kitchen. It’s easy to miss this gem, home to some interesting artefacts, including a large plate marked with the crowned ostrich feathers of Arthur, Prince of Wales.

The Tiltyard Café is the only surviving tower of five built by Henry VIII as viewing platforms, where dignitaries and courtiers watched tournaments in the Tiltyard below.

Kitchen at Hampton Court Palace; Stairs to kitchen. Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Line drawing of kitchens.

The Gardens

Over sixty acres of stunning gardens are also waiting to be explored at Hampton Court Palace. Cardinal Wolsey was probably the first to build ornamental gardens on site, but Henry VIII established the magnificent gardens that the palace would subsequently become renowned for, which surpassed, in beauty and size, those of all other royal residences.

The sunken pond gardens, once Wolsey’s fishponds, look and smell exquisite in early summer, when they are bursting with blossom and over-run with flowers. In March 1528, Anne Boleyn dined with Thomas Heneage at Windsor and commented on these very fishponds, saying how pleasing it would be during Lent to have some freshwater shrimps or carp from Wolsey’s famous ponds.

To understand what the gardens were like in Anne’s day, visit the recreated gardens in Chapel Court, inspired by those visible in the background of The Family of Henry VIII that hangs in the Haunted Gallery. The gardens are planted with flowers and herbs that would have been available in the sixteenth century, enclosed by green and white striped low fencing and guarded by heraldic beasts on poles.

Apart from the impressive gardens, when completed, Hampton Court Palace boasted tennis courts, bowling alleys, a hunting park and even a multiple garderobe. Henry’s children spent time indulging in Hampton Court’s splendour as heirs to the throne and in their own right as Tudor kings and queens.

Like her mother, Elizabeth I visited Hampton Court Palace shortly after her coronation. It is here that her first official summer progress concluded in 1559. One wonders whether Elizabeth took note of her parents’ entwined initials in the great hall or thought about her mother’s first triumphant visit to the palace as queen when she – and not the expected male heir – was safely cradled in her womb.

For those of us wanting to follow in Anne’s footsteps or, more generally, for the Tudor enthusiast, Hampton Court has no equal. So much of Henry VIII’s private drama – from heartbreak to triumph – played out within its walls. Listen closely as they echo with the footsteps of its past inhabitants and play back the memories of those distant, cataclysmic events.

We’ll be visiting Hampton Court Palace as part of The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn tour from 2 – 8 September 2024. Dan Jackson, Buildings Curator at Historic Royal Palaces, will be our guide, taking us behind the scenes to see hidden areas off tourist trail. There are just three places remaining – don’t miss out! Book your space here.